|

|

|

|

|

|

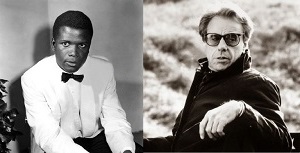

Poitier and Bogdanovich

Peter Bogdanovich dedicated a chapter of his 2004 book Who the Devil’s In It to Sidney Poitier, writing that “Poitier was to the movies what Jackie Robinson was to baseball.” I turned to that chapter for comfort when I learned that Poitier had died less than 24 hours after I found out Bogdanovich had passed. It had already been a rough few days for celebrity deaths - first John Madden’s and then Betty White’s. Bogdanovich’s had stung a little more, and then Poitier’s was the hardest. Madden often quoted his former colleague Pat Summerall’s question when judging someone’s impact: Could the history of that person’s field be told without mentioning that person’s name. With Poitier the answer to Summerall’s question was an emphatic “No.” Black film stars existed before Poitier, including Josephine Baker, Paul Robeson, Dorothy Dandridge and Lena Horne, but they and others were hamstrung by blatant bigotry, local censorship and risk-averse studios. Poitier fought for and got opportunities denied to his predecessors. For his very first film Poitier co-starred with Richard Widmark in No Way Out, playing a determined young doctor held captive by Widmark’s racist fugitive. By that point Widmark had become a major star, while Poitier was a 23-year-old unknown, but he matched Widmark beat for beat. Even then, Poitier had the intensity and gravitas that would come to define his career. Seven years later he garnered his first Oscar nomination opposite Tony Curtis in The Defiant Ones. In 1961 Poitier gave my favorite performance of his, in A Raisin in the Sun. Continuing a role he originated on Broadway, Poitier shined as Walter Younger, a poor but ambitious man with big dreams. Unlike many of Poitier’s other characters, Walter didn’t have it all together. He’s desperate for money and to prove himself as a provider for his family. It would have been easy to play Walter as either overly sympathetic or as a victim. Poitier did neither, instead digging deep and connecting with Walter on an empathetic human level. He made Walter relatable, compelling, at times heartbreaking, but also proud. The scene towards the end of the film where Walter stands his ground for his family has lost none of its power more than 60 years later. In 1964 Poitier became the first black man to win a Best Actor Oscar for his role in Lilies of the Field. In 1967, he starred in three hit films, To Sir, With Love as an American teaching roughneck students in the UK, Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner as part of a then-groundbreaking interracial romance, and most notably In the Heat of the Night as a Philadelphia cop in the Deep South. It’s Night that still resonates most today. In many of his prior films Poitier played stoic men who endured vitriolic racism without fighting back, but he always let us see the fire underneath. In this film he did so again at first, while slowly cluing us in that there’s only so much he could take. Keep in mind that the film debuted in August 1967. Martin Luther King’s non-violent civil rights ideas, to which Poitier personally subscribed, were challenged by the new Black Panther Party among others. Clashes between white police and African American residents in Detroit led to full scale riots just weeks before the film’s release. Now here onscreen was Sidney Poitier’s character being demeaned by cops and others in Jim Crow country. But not for long. After the redneck police chief insultingly asks “’Virgil?” That's a funny name for a n***er boy to come from Philadelphia. What do they call you up there?” Poitier lets his pride and dignity rise with each word as he exclaims “They call me Mr. Tibbs!”. Of course, Mr. Tibbs and the man who played him were just getting warmed up. After a racist white suspect slaps him, Tibbs slaps him right back. I’ve tried to imagine how it must have felt for black moviegoers, after so many years seeing themselves onscreen degraded by lazy stereotypes, to see Poitier literally striking a blow against those that would degrade them further. The truth is that as a white man in 2022, I can’t fully comprehend that. Like Jackie Robinson, Poitier carried the burden coming with being “the first” with courage, determination and grace. In one way Poitier’s burden stood even greater. By the time Robinson retired after nine seasons with the Dodgers, other black stars such as Roy Campanella, Willie Mays, Hank Aaron and Ernie Banks were all in the majors. Nine years after Poitier garnered his Oscar nomination, he was still the only name above the title African American star. Rather than understanding Poitier’s talents and success as evidence of what this untapped population of actors could do if only given the chance, film studios and producers treated him like a unicorn, a one-off. This meant Poitier viewing every choice, every character and every performance as representing an entire race onscreen to both black and white audiences. He later remarked that he would have liked to play a villain occasionally but felt he couldn’t because of how it would be seen through the racial lens. Poitier did branch out though, moving to directing in the 1970s, with films such as Buck and the Preacher, Uptown Saturday Night, and A Piece of the Action. Now that Hollywood was finally, slowly, developing other black stars, Poitier proved he had other sides than the serious ones he’d shown before. He developed a flair for comedy both as an actor and director. Even here he was a trailblazer. With the Gene Wilder-Richard Pryor comedy Stir Crazy, Poitier became the first black director of a $100 million grossing film. Poitier’s death brought me back to one night and one day. The night came in 2002, when the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences awarded Poitier an honorary Oscar to go with the one he won 38 years earlier. This is back when the Academy actually televised the honorary awards, and it introduced Poitier with a short video directed by Kasi Lemmons. Seeing current African American film stars such as Denzel Washington, Will Smith and Halle Berry describe what Poitier and his films meant to them was moving enough. Then when they all looked into the camera and said, “Thank you Sidney,” I got a lump in my throat as I’m sure most people watching did. The day came 13 years later when I was visiting the Bahamas, where Poitier was born and raised. As my cab in Nassau crossed the Sidney Poitier Bridge, I beamed a big smile. The cabbie asked why, and I briefly explained who Poitier was and what he meant. The cabbie didn’t get it, but I felt just a little closer to a film legend. My words have taken me as far as I can go, so I’ll turn it back over to Bogdanovich. He closed his Poitier chapter with “As a special human being he (Poitier) represents far more than the sum of his roles, because finally, the part he was given to play in life, and in which he triumphed, is among the toughest of all.” Bogdanovich’s book profiled 25 movie stars including Poitier. For each of them Bogdanovich explored why they were stars, what they brought to their films, and who they were as people. Seven years earlier Bogdanovich wrote Who the Devil Made It, which examined 16 filmmakers including Alfred Hitchcock, Howard Hawks and Sidney Lumet. Many of these people Bogdanovich had known personally. Both books devote much of their pages to interviews Bogdanovich conducted with the subjects. Bogdanovich authored 15 books in all, biographies of John Ford, Orson Welles and Fritz Lang among them. Of course Bogdanovich became an acclaimed filmmaker in his own right at one point leading the “New Hollywood” charge in the early 70s with classics such as The Last Picture Show, What’s Up Doc?, and Paper Moon. Unfortunately, his career behind the camera gradually fizzled the rest of the decade. While he still had the occasional success, such as Mask and The Cat’s Meow, he never had the landmark career he seemed destined for from his early work. He became more famous for his love affairs with Cybill Shepherd and the late Dorothy Stratten than for what he put on screen. Of his filmography I’ve only seen the five films above along with his last effort The Great Buster, a documentary on the great silent film actor/director Buster Keaton. So, I’ll leave it to others to analyze him as a director. I will cherish him more as a historian, perhaps the historian of the classic Hollywood studio era. Bogdanovich absorbed movies like a sponge in his youth. Roger Ebert once described how in the early 60s Bogdanovich would frequently stay up to all hours of the night and morning to watch lesser-known movies on TV. In those pre-home video, pre-streaming days, that would often be the only way to see certain films. Through connections, charm, and hustle Bogdanovich gradually ingratiated himself to many of the stars and directors whose films he grew up watching. They felt comfortable around him, perhaps because he knew their work so well, perhaps because he would celebrate their careers even though most were fading by that time. Regardless, his work helped me learn more about these men and women long after they had passed. Through him I got a small taste of what it would be like to be around these people, both on and off the set. Bogdanovich may have been even better as a speaker than he was as a writer, which is why he was regularly seen on Turner Classic Movies and heard on DVD commentaries. I was lucky enough to hear him speak at some book signings and other events. He could deliver an anecdote like few others could. It helped that he also folded in spot-on impressions of the people he was describing. A couple of my favorites: He got in an elevator with Hitchcock, who started discussing a chilling murder scene. As more people entered the elevator Hitch continued to build the suspense. Finally, when he was almost at the climax the elevator reached his floor, and he exited. Right after he and Hitch got off, Bogdanovich eagerly asked “So, what happened?” “Oh, nothing,” Hitchcock replied. “That’s just my elevator story.” Another time he and Cary Grant went to a gala and checked in at the front table. “Your name please,” said the lady while looking down at her papers. “Cary Grant” the star answered. The lady looked up and saw a man older than how Grant appeared on-screen. “You don’t look like Cary Grant,” she told him. “I know,” he responded. “Nobody does.” While funny and amusing, these stories also give a glimpse into these men’s personalities. Bogdanovich was a walking window into the past. For his film swan song, The Great Buster, Bogdanovich made an interesting choice. He spent the first half of the film going through all the peaks and valleys of Keaton’s career and then doubled back in the second half to take a deep dive into what made the man so funny and innovative. Hemingway famously said that all true stories end in death, but Bogdanovich wanted audiences to leave the film feeling Keaton to be as vibrant as he was when he worked a century ago. Bogdanovich always wanted to protect film history, especially when his friends were involved. He defended Orson Welles in 1972 when Pauline Kael diminished the man’s contribution to Citizen Kane and did so again 48 years later when the film Mank did the same. Bogdanovich worked tirelessly to complete The Other Side of the Wind, which Welles filmed in the early 70s but never finished. In 2018, thanks to Bogdanovich, his team, Netflix, and many others we were able to see one last masterpiece from the maverick director who had passed 33 years prior. To truly love anything, be it a profession, a discipline, a form of art or even a hobby, one must cherish its history. Both Poitier and Bogdanovich made their mark on film history. The first shaped that history through breaking barriers; the second kept history alive and relevant. Film history, and film itself, is greater for them having been a part of it. Adam Spector February 1, 2022 Contact us: |

|