|

|

Leonard Nimoy

When I read that Leonard Nimoy had died, my thoughts turned to a nine-year-old boy watching Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan. That was me more than 32 years ago, but at that moment it might as well have been yesterday. I had heard a rumor that Spock might die in the movie, but actually seeing it unfold was too much. As the credits rolled, I started crying. Now I do not mean that I had to wipe away a couple of tears. I was sobbing because I just couldn’t believe that Spock was gone.

Why did a fictional character’s death mean so much? One reason could be how brilliantly the death scene was staged and executed. I wrote about that scene as part of a column a few years ago. The scene’s power came from how it captured both who Spock was and his friendship with Kirk. He died to save the ship, for him a purely logical decision, true to his Vulcan side. Then his last conversation with Kirk showed Spock’s human side, with his immortal words, “I have been, and always shall be your friend.”

Still, the scene itself only explains part of the impact of Spock’s death. The other part came from who that character was throughout the TV show and movies. When I saw “Star Trek” as a little boy while sitting with my Dad, I latched onto Spock immediately. Kirk was the traditional American hero, handsome, swaggering, and bold. He was the ‘captain of the football team,” who always got the girl. Spock was different, not just from Kirk but from any other character in popular culture. He was cerebral, analytical, and, of course, logical. The show spoke of going where no man had gone before, and Spock best represented that goal. He was the one most open to new ideas. On an episode where he and Kirk encountered the Organians, a race that had moved beyond physical desires and conflicts, Spock said, “the Organians are as far above us on the evolutionary scale as we are above the amoeba.” He got it, he always understood. Spock epitomized what was unique and exciting about Star Trek and, to some extent, science fiction in general.

Only later did I truly understand why Spock resonated. Anyone who, like me, often felt like an outsider could identify with Spock. Spock was half-Vulcan, half human and did not belong anywhere. He struggled with integrating those two parts of himself, but he came out ahead and excelled. Of course I was not Spock, but I could see myself in him. In many ways, he was who I wanted to be.

Leonard Nimoy was not Spock either (as his first book clearly stated), but he provided the character with so much of what made him relatable. The writers made Spock stoic, but Nimoy made him cool. He did so much even when Spock was not talking, through his eyes, expressions and the tiniest of gestures. Nimoy illustrated a man observing and figuring out a situation so he could be one step ahead. When Spock was talking, Nimoy always had just the right timing and inflections. Nimoy’s own warmth, and, yes, humanity always came through, giving Spock an added depth. Like Spock, Nimoy had to overcome challenges. He had to be convincing as a full, rich character while often limited in what he could visibly show. But, also like Spock, Nimoy succeeded not in spite of but because of the challenges. Nimoy could convey more by Spock raising an eyebrow or saying “fascinating” than other actors could with pages of dialogue.

Nimoy brought even more to Spock than his talents as an actor. He helped shape the character and his development. It was Nimoy who worked with the writers to invent the famous Vulcan nerve pinch. He famously based the Vulcan salute on the Jewish priests blessing. It was not easy for a young Leonard Nimoy to grow up Jewish in a Catholic Boston neighborhood. He later said, “I knew what it meant to be part of a minority, in some cases an outcast minority.” Unlike other celebrities, Nimoy never hid his Jewishness. He embraced it and let it influence his art, including Spock. Nimoy blended his own culture with Spock’s Vulcan culture. As a Jewish kid, I could see in the Vulcan focus on reason, education, peace and selflessness, a reflection of the best parts of my faith. Nimoy became a rarity in a Hollywood: a true role model.

It took me a while to grasp that Nimoy was more than just Spock. I saw him play Golda Meir’s husband in a TV movie. My dad owned a book of his poetry. Together we would watch him host “In Search Of,” a show about mysteries and unexplained phenomena. Looking back, that show was a little cheesy, but it didn’t matter. If Leonard Nimoy said something was worth exploring, who could argue? Even in the Star Trek world, Nimoy wore multiple hats. He directed Star Trek III: The Search for Spock, co-wrote Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country, and did both with Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home. Outside the Trek world he directed Three Men and a Baby. As a filmmaker he showed a light touch and gave all the cast a chance to shine. He also had a light touch elsewhere, never taking himself too seriously. Nimoy frequently poked fun at his own persona, most notably in two “Simpsons” episodes.

Nimoy gradually grew to accept that he and Spock were intertwined. For his many accomplishments, he was, first and foremost (as the title of his later book acknowledged) the man who brought Spock to life. So it was for me with Nimoy’s death. Although stunned by the news, I went back to my work and had dinner with friends that evening. Afterwards, I played my Star Trek II DVD. I just had to go back to Spock’s death scene and be that nine-year-old boy again. Then I put in Star Trek III. In the years between those two movies fans anticipated that Spock would come back. My cousin freeze-framed Spock placing his hand on McCoy in Star Trek II as proof that he would be resurrected. But I never took that for granted (unlike now, were you assume that franchise lynchpins will die and come back to life). Finally, at the end of Star Trek III, Nimoy emerged as Spock again. After reacquainting himself with Kirk and the others, Nimoy/Spock did his trademark eyebrow raise and, at long last, I rejoiced. Spock was back and all was right with the world. I wish real life was that kind.

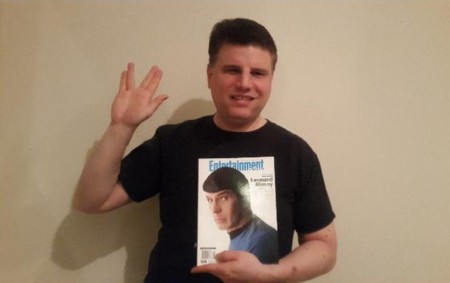

I am searching for the best words to wrap up, but they are failing me. “Live Long and Prosper” became Spock’s mantra. As many people, and a clever billboard pointed out, Nimoy did just that. It’s easy but fitting to go back to the end of Star Trek II -- Kirk eulogizing that, “of my friend I can say only this: of all the souls I have encountered in my travels, his was the most ... human.” Then McCoy later adding, “He’s not really dead as long as we remember him.” Both fitting tributes for Nimoy, but not quite sufficient. I suppose it is not words but a picture that can truly sum up what I am feeling. So, forgive me. You know this is coming but I’m doing it anyway:

Adam Spector

April 1, 2015

Contact us:  Membership Membership

For members only:  E-Mailing List

E-Mailing List

Ushers Ushers

Website Website

All

Else All

Else

|