|

|

|

|

|

September 2006 Last updated on September 17, 2006. Please check back later for additions. Contents

This Film Is Not Yet Rated: An Interview With Kirby Dick JUST ADDED 9-17 This Film Is Not Yet Rated: An Interview with Director Kirby Dick

By Jacqueline Arrowsmith Audience Q&A With Kirby Dick

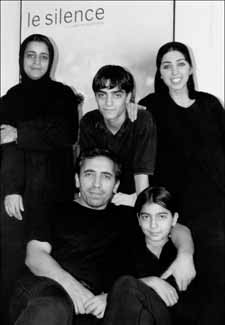

After a screening for DC Film Society Members at Landmark Theater's E Street Theater on September 12, Kirby Dick answered questions from the audience. DCFS Director Michael Kyrioglou moderated. Kicking His Way to Stardom: Tony JaaBy Paul Jaskunas, DC Film Society Member Hollywoodland: Audience Q&A With Director Allen CoulterBy Ron Gordner, DC Film Society Member Drinking Games: an Interview with Beerfest's Erik Stolhanske and Steve LemmeBy Jim Shippey, DC Film Society Member Seen in Edinburgh: Driving Lessons--Press Conference CommentsBy James McCaskill, DC Film Society Member The 2006 Munich International Film FestivalBy Leslie Weisman, DC Film Society Member This year, in addition to its customary screening of 200+ films from more than forty countries, many of them world premieres, and "podium discussions" with dozens of notable directors, Filmfest München focused its telephoto lens on three of today's filmic giants. One of these has extended his legacy so that it now encompasses a family of five, whose exile from their homeland has not kept them from making incisive, award-winning films about it--or from hoping one day to return to it. But perhaps, we should take our singular cineastes in geographical order... Kudos to a hometown fella: Barry Levinson Filmfest München's prestigious CineMerit Award, bestowed each year upon "an outstanding personality in the international film community for extraordinary contributions to motion pictures as an art form" (previous recipients include Geraldine Chaplin, Milos Forman and Jacqueline Bisset) this year honored our own Barry Levinson, auteur of such classic films as Diner, Rain Man, Wag the Dog and Good Morning, Vietnam. In a relaxed but illuminating conversation with Filmfest programmer Robert Fischer, Levinson held forth about the extent to which his films are personal ("Obviously they express a lot of the feelings I have, but I've always tried to make myself as anonymous as possible, so that you're not aware of how it got done, you're not aware of the shots") and the secret behind his productiveness ("I write extremely quickly; it feels like I'm doing dictation"). How does he develop his story lines and characters? "If I can launch the characters with certain ideas, they will take over the piece, to take me where it needs to go. The story begins to tell itself, the characters will surprise me, take me to places I don't expect. If I tried to do an outline, I'd still be working on Diner!" Which of his characters are closest to him? "They're all a part of me; I'm actually like some of the women in my films, like the one who works in a television station, because I worked in a television station. But--Sixty-Six [his 2003 novel, written as the basis for a possible film in the Diner series] is probably the closest I'll ever come to me." While Diner, Avalon, Tin Man and Liberty Heights may closely reflect his Weltanschauung, "it's not intentional--I try to be as invisible as possible." Mention of the book enabled an easy segue into Levinson's career as a scriptwriter, where he cut his teeth under Mel Brooks' tutelage before becoming a director. "It was the best apprenticeship you could have. I worked with him for three years on two movies, Silent Movie [where the only spoken word is uttered by mime Marcel Marceau, who says "Non!"] and High Anxiety. We would meet every morning for breakfast, work on the script, shoot some scenes... Even though we have different approaches, I learned so much from him." What made him decide to become a director? "I never had an ambition of what I wanted to do or where I wanted to go. My number-one ambition as a boy was not to work in my father's store." Levinson regaled the audience with the tale of how he got into filmmaking "by accident." It seems that a friend of his named George was taking acting classes, and needed a ride. Levinson agreed to give him a lift, and when George got out of the car, he insisted that Levinson accompany him so he wouldn't be sitting outside by himself. Not having any interest in acting, but finding no way to agreeably decline, Levinson went in--and was immediately issued an ultimatum by the instructor: If you want to stay here, you'll have to participate. It didn't take long before Levinson was hooked. And his buddy? George Jung soon dropped out, and their paths diverged. Years later, watching the film Blow, Levinson learned what became of his friend. Seems that in the intervening years, while Barry Levinson was honing his writing and directing skills, George Jung was honing other skills, and had achieved a fame of his own: as the biggest cocaine dealer in North America. (He wound up in prison.) But back to Barry. First, of course, came Diner, which was not the immediate hit one might expect. Daily Variety called it "dark and depressing," said Levinson, which puzzled him. But then Pauline Kael gave it a great review, and it took off. "If you're not working within a specific genre," he added, "sometimes critics don't know what to do [with a film], how to handle it." The diner in Diner, we learned, was transported from New Jersey to Baltimore, then returned to NJ, then back to Baltimore, which at last bought it and settled it there--and turned it into a voc-ed school. The style of Diner, where a lot of the dialogue seems to be improvised, was picked up again later in television, noted Fischer, on shows like Homicide. Levinson agreed: "It's like life, where a lot of times you don't say exactly what you mean, where you hesitate, and that's what I wanted to get into the characters. The inarticulate nature of what we say may have great significance, but it gets hidden in the messiness of it all, as opposed to saying specifically what we want, which we don't generally do." Where did this come from? "As an 11-year old, I was struck by the exchange in Paddy Chayevsky's Marty which I saw on TV, where two guys are talking: 'Whaddya wanna do, Marty?' 'I don' know, whadda you wanna do?'--so natural, so normal, so everyday. So I determined to write dialogue like that. And Diner is all that kind of dialogue." "And then you picked that up for Homicide. It changed the language of TV." "Well, it's dialogue-driven, which kind of drives the producers crazy, because they want to have an action- driven promo to advertise it. I wanted to explore how working in a job like that day in and day out affects people, changes people." For Rain Man, Levinson decided to strip it down to the bare essentials: two brothers in a car, and the character development that takes place as they travel together. Rain Man helped bring autism out into the open, he told us, helped people to recognize, identify and treat it, and not be ashamed of it. Dustin Hoffman asked Levinson how he wanted him to do the pitching motion that was one of the physical aspects of Raymond's autism. Levinson told him to think of pitching a ball, to get into the rhythm of it. But that was only the physical part, not the conceptual part, and Hoffman needed more. So Levinson came up with the idea of the old Abbott and Costello routine, and told Hoffman to "think of it as a mantra" that he would repeat along with the arm motion. It clicked. Levinson later spoke with psychologists, who said an autistic person might indeed repeat a phrase like this as a sort of mantra. What does the future hold for Barry Levinson? His latest film, Man of the Year, about a Jon Stewart-like talk-show host who runs for the presidency, is opening in October, and features Robin Williams, Laura Linney, and Christopher Walken. And watch for a triple-DVD set of Bugsy. (Ignore any hype about a "Brilliant" film with Scarlett Johansson; the blurb was premature. The film fell through.) What does he see for the future of cinema? "It's so much easier to make and distribute films now. I think we're at the beginning of a big revolutionary change; you're no longer bound by the old conventions." And Barry Levinson will be right at the plate. Mike Figgis: Man with a four-track mind One of the most gratifying surprises of this year's Filmfest München was the revelation of an entire body of remarkable film and television work that many of us had never seen, or were even aware of. Renowned British filmmaker Mike Figgis, perhaps best known in the U.S. for Leaving Las Vegas, the groundbreaking Timecode, and memorable directing gigs with "The Sopranos," was honored with a retrospective. The first ever to encompass his entire oeuvre, it spanned 32 films and TV programs, among them some 10 "Hollywood Conversations" featuring intimate interviews with Mel Gibson, Jodie Foster, Salma Hayek, and others. As his pièce de résistance, Figgis wowed a full house with a "live mix" of Timecode. In a podium discussion immediately preceding the live mix, Figgis told the eager audience who besieged the podium with cameras, pens and programs, and were finally persuaded to take their seats--that he has done 15-20 of these "live mixes," in which he plays with the pacing, dialogue, and score of the four split-screen stories. Noting that Figgis had added a fifth soundtrack for this screening, the Filmfest programmer observed that the mixing of Timecode (as indeed the film itself) can be seen on so many levels--cinematic, musical, philosophical, artistic--that it concerns "not only cinema as we know it, but the future of cinema as we know it." "What's incredible for me is that it's a new film every time," Figgis told the audience. The film, released in 2000, is "not finished; it never will be finished. There's nothing like doing it in a live theater, because things can go wrong," he added. "[But] the more I do it, the more I feel competent to take a chance and try something new... I can't think of another experience in my career of making films that's anything like this." Confessing that he gets upset when people say "It's a nice gimmick" or "It's a nice card trick," Figgis avowed that it's a "very serious genre," not a "gimmick" or "card trick," and that he is "always looking for a new way to use cinema... [while] I love cinema, I'm also completely bored with it." Asked about the scene in which the young filmmaker comes in to passionately pitch her film, which is structured like Timecode, and is ridiculed--"it's almost like you're ridiculing yourself"--Figgis confessed that critics can be a bear. They can be "insightful once in a while," but "they also can be completely mindlessly cruel and destructive." And on occasion pretentious, to the point where "I've had conversations about my work that I don't understand" and "I've felt stupid talking about my own work." And then there are those find "more in my films than I put into them." So he inserted two characters who would play out that "Andy Warhol sort of situation," where "if I say it's art, it's art," and anticipate the type of dialogue that might ensue in some quarters when the film came out. Figgis said he thought it was "kind of an interesting dialogue to have within the film," because "we've turned the audience into a bunch of zombies in the dark; we are no longer proactive, we are reactive... it's where we go to kind of zone out, but we don't participate. We did it in kind of a comic way, but I agree with everything she says." Recalling Hitchcock's famous long takes in Rope and Under Capricorn, which the advent of sound ostensibly favored, Figgis was asked whether Timecode heralded their resurgence. The operative factor is the kind of film you're doing, he answered, although long takes should not be overused: "Film is not theater." And while the inspiration for Timecode derived, in fact, from his interest in the new video equipment, it may be that the "cinematic cart is pulling the horse: cinema equipment is leading cinema innovation." An accomplished musician, Figgis conceives his films like a string quartet, where each player goes off into a room to practice, then all come together to make it work as a whole. The analogy is not superficial: Figgis actually used music paper to write the script for Timecode, with each line representing a minute of screen time, then went about teaching the cast of 30 to "read music as film," giving each person his own dialogue and counting on the four separate tracks to come together when the filming started. Each time he made a change, the actors would make the corresponding change on the music paper. What's great about these live mixes, Figgis said, is that it puts you back in touch with the audience; it's like theater (an instructive counterpoint to his earlier assertion that film, in its usual state, is not theater), where the audience really doesn't know what will come next, and he can feed off their anticipation and their presence. (At the live mix later that evening, we learned some interesting "insider stuff" about the film. Figgis told us that in the original film, he was at the bottom right-hand camera. In production, he began shooting one film a day, but when the studio complained, increased it to two a day. When it came to the earthquake, he told the actors to do their own "earthquake acting," their own "vision," as it were, compelling him to employ what he called "earthquake choreography" for the scene. The live mix itself included rewinds of selected shots and scenes, featured certain actors more than others, and included additional, and different, music. It was not, he emphasized, what you'll find on the DVD.) Asked to say a few words about scoring his films, Figgis affirmed that music is key: "I could play Mahler and have a dog piss against the wall and you'd find it incredibly profound and moving." On the other hand, using great music can be a problem, not only bringing with it its own associations, but heightening the emotional impact of whatever scene it accompanies, which can be problematic for the director: nothing can follow it. Proceeding to the "Hollywood Conversations," Figgis said that in conceiving them, he decided to pare it down to bare-bones, with just a single camera on the person being interviewed. Was part of his motivation to get back at Hollywood for treating him shabbily? Figgis firmly denied any bad feelings, declaring that he never wanted to take revenge on Hollywood, and was in fact "entirely complicit": anyone who gets into the game, he said, knows that the same people who fawn over you one day will ignore you the next, and be your best buddy the day after; it's the business. When it comes to Hollywood executives, Figgis said, their power gives them the ability to say the most outrageous, insulting things to people: "If they said some of those things to you in a pub in London, you'd say 'Please step outside,' but it's all because of the money. How low will you go for the money?" Mel Gibson expressed similar sentiments to Mike in his 1999 "Hollywood Conversations" interview (see below). And what does the future hold for Mike Figgis? If you were eagerly anticipating Guilty Pleasure, announced in late 2004 as "a thriller about a young couple who engage in a ménage à trois as a last sexual fling before their wedding," yours (pleasure, that is, guilty or otherwise) will have to be put on hold. The studio had problems with the script, and asked Mike to fix it. He set assiduously to work--not sure where the problem was, but willing to rework the script to give them what they wanted--rewrote the first two acts, and sent it off. Their reply? The first two acts were fine; it was the third act that needed work. Guilty Pleasure: not coming to a theater near you, at least for a while (and Figgis left the impression that it may never see the light of day). But a whole slew of Figgis films and TV shows did come to Filmfest München. I was able to see a choice few of them, including one of the "Hollywood Conversations," a series of half-hour interviews with actors and directors that Figgis produced and conducted for British TV. (They were later published in an anthology, "Projections 10: Hollywood Film-Makers on Film-Making," Faber & Faber, February 2000.) By luck or skill, the one I managed to see was the interview with no-holds-barred Mel Gibson. It did not disappoint. In a wide-ranging, stunningly candid conversation, Gibson heartily admits that he was "a great liar" as a boy growing up in Australia. He and Figgis then commiserate over the audition process--"You feel humiliated, watching [actors] prostitute themselves," says Gibson--and share their mutual, deep-seated fear of Christopher Walken who, they say, loves grim, horrific things and torture (we can only hope it stops at fictional representations of them) even more than Gibson does. When it comes to the opposite sex, Gibson readily admits that they are "way above us"; men are the "storytellers." On the opposite side of the moral equation are producers, de facto arbiters of the "social contract" that rules Hollywood. Recalling some of their experiences in Hollywood, Gibson and Figgis agree on the common term that people in the business use when they get ripped off, or make a costly mistake: "school fees." But you can't get mad, says Gibson equably; it's a given that you're going to get abused by people you're going to have to work with again. So you can't take it personally. "You have to choose what level of integrity you're coming in at. You need that kind of cockroach resilience to survive here." Human Rights in Film Survival of a more urgent kind was the subject of four films co-presented with Human Rights Watch. Land of the Blind (Robert Edwards, Great Britain/USA, 2006), an allegorical drama about the battle of freedom and idealism against political repression and corruption, is set in an unidentified future time and place (although 1984 is not far off), and features Ralph Fiennes as a soldier whose curiosity about the political prisoner (Donald Sutherland) he is assigned to guard by the country's Duce-like dictator leads him in a downward spiral that careens out of control. Beginning as a Pythonesque slapstick-satire, it proceeds to commentary, both sharp-edged ("If voting could ever really change anything, it would be illegal") and subtle (after viciously killing his subordinate, who failed, the leader advises his dumbstruck colleague to read The 7 Secrets of Highly Effective People, adding: "It helped me tremendously"), but never really settles on one genre. There is an implicit indictment of the media--when Sutherland blinks TORTURE with his eyes, it is duly translated on TV by blithely blabbermouthed reporters; and in a send-up of a former president, the leader and his wife oozingly call each other "Mommy" and "Daddy." Returning to the literary, when Sutherland, now the leader, gathers his underlings around him, he exhorts them to dip their hands in the slain leader's blood--Julius Caesar, anyone? He then proceeds to become as power-hungry and corrupt as the leader he and Fiennes joined forces to overthrow--even more so, instituting a mullah-like theocracy with absolute power over not only his subjects' actions, but their thoughts. Cautionary tale, or fairy tale? Maybe a bit of both. The next film thrust us into a stark reality whose cautionary value is well known, and whose horrors one could only wish were but fairy tales. KZ (Rex Bloomstein, Great Britain, 2005), is a potent study in dichotomies that makes its points deliberately, yet powerfully. Beginning with the bus that brings a score of chatty tourists to one of Austria's most infamous landmarks, the erstwhile concentration camp (Konzentrationslager, or "KZ") Mauthausen, it ends with the ineffable solitude of the camp's director, whose job has become his mission--at an increasingly untenable mental and emotional cost. Entering the camp, visitors are greeted by a sober yet friendly baritone voice warning them that they will see but a watered-down version of what happened there, because to see what really happened would drive them mad. "And we want you to return with a sound mind, to further the cause of justice, peace, and truth." It seems to have the desired effect on at least some, who later give their impressions. A Nigerian man, asked what he learned there, goes to the heart of it, saying that the greatest horrors start with small indignities, and that if we learn to recognize them early on, we can stop them from growing out of control. (Those whose first taste of French literature was Antoine de Saint-Exupéry's "The Little Prince" will be time-capsuled back to its lesson of the baobab trees, small, yet insidiously voracious, which must be extirpated at the root to prevent them from overtaking entire forests.) The director of the site admits that he is obsessively committed to its mission, reading, watching, and buying everything he can get his hands on relating to the Holocaust, on which he has become something of an authority. His tour for the camera crew includes a shot of the road signs for the camp which, he notes with disbelieving irony, are contingent to, and the same color as, the sign for the nearby inn and beer hall, where troubadours rousingly sing Mauthausen's praises as they greet the tourists. Interviews with residents produce a range of reactions, with most perhaps predictably defensive about their hometown or choice of residence. Interestingly, age is not an augur of reactions; both those born after the war and those who lived there at the time are equally blasé about the elephant in their room. Only one woman somewhat nervously acknowledges the inherent embarrassment, or at least discomfiting awareness, that informs her choice to live there. The most telling sequence may be the interview with three SS widows who reminisce nostalgically, and with undisguised pride in their husbands' importance--fueled in no small measure, one suspects, by self-importance--about the "good old days." Reluctantly compelled by the interviewer's simple but insistent questions to recall what else was happening under their very noses, and at their own husbands' hands or under their supervision, two of the three begin to remember--"mounds" of living bodies piled up in the street like garbage, "babies and children... they were still moving,... the soldiers started shooting into them... then they stopped... the bodies were left to rot in the sun for days," says one, her friend and neighbor of some 60 years looking at her in disbelief. (Of course, her most indelible memory of those times was her wedding, a lavish affair held in the camp itself, with inmates--Theresienstadt-like presentable--providing the "entertainment.") The local priest, asked if he ever gets the question: "Where was God?" says no, he hasn't. But he has asked himself the question--and hasn't found an answer. Introducing the film and its director, Rex Bloomstein, the Filmfest programmer noted that films such as this exemplified fest director Andreas Ströhl's conviction that the supposed "smallness" of documentaries was more a question of form and budget, than one of importance or resonance. (Affirming this judgment, director Barry Levinson later called the film Journey to Justice, which also deals with the Holocaust, "a documentary with the emotional power of a feature film." More on this film below.) Asked what inspired him to make KZ, Bloomstein told the audience that it was the appalling incongruity of the road signs and the beer hall, both within shouting distance of the camp, that resonated with him, and convinced him to make the film. At the same time, he acknowledged, the estimated 4,000 existing documentaries on the Holocaust beg the question of why there should be yet another: "What else is there to say?" The film itself answers this question powerfully. But further proof was to come. At a Q&A following the screening, several in the audience identified themselves as children or grandchildren of survivors, or of fathers who worked in a concentration camp or served in the German army during the war. In an odd convergence, their wildly disparate experiences then, yielded similar reactions now: Whether survivors, perpetrators or unseeing observers, none want to discuss the subject to this day, even with their families. This microcosm alone offered, if one is needed, a telling answer to those questions. The experience of survivors was recounted both filmically and personally as a sold-out theater followed Howard Triest's on-site narration of the story of his return to the land he fled as a teenager after years of terror at the hands of the Nazis in Journey to Justice (Steve Palackdharry, USA, 2005). His story was of more than historical interest here in the Munich Film Museum, for Munich was the home of his family for generations, so assimilated they felt "more German than Jewish; the fact that the [Nazis] later defined the Jewish religion as a race didn't alter that." Yet it was from here that they were torn, to die horrific deaths, with Howard and his younger sister Margot--after months of running and riding, hiding and being hidden, pursued, and occasionally helped--the only ones to escape. (Margot also helped 10 other children escape.) The film uses never-before-seen documents, photos, and archival footage, much of it taken from Howard Triest's own files, to recount his harrowing journey from Munich to America, where, just a few years later, he joined the Army and served as an interpreter at the Nuremberg trials. He recalled the equanimity with which Nazi officials described, "like bureaucrats," the inhuman torture and degradation inflicted on the camps' inmates, taking pride in having "exceeded their quotas." (Nuremberg, he reminded the audience, was chosen as the site of the trials because of the infamous Nuremberg Laws, which the Nazis drew up to put a "legal" stamp on their actions.) Recalling how he somehow managed to maintain his composure before Rudolf Hoess, the commandant at Auschwitz, where his parents were murdered, Triest acknowledged that he believed the sentence Hoess and others received--hanging--was "too easy for them." Effectively mixing past and present--at times Triest becomes a photograph, observing the interviews or silently commenting on a still--Palackdharry's cinematic achievement is ably abetted by the photographic skill of Howard's son Glenn, who in a post-screening discussion admitted that he cannot completely relax in Germany, unlike his father, who now can. But his father has more than earned that ease, which was felt by all during the shoot, thanks in large part to the director; Margot told the audience that his open, honest, and relaxed manner enabled her to feel free to say things she had not even told her children, who were astonished and moved when they saw the film. But children are the next generation, and Howard and Margot's meeting with the young couple who now live in their former Munich home is illuminating and heartwarming, as they exhibit a friendliness, openness and curiosity, and a willingness to question "accepted truths," that contrasts sharply with what the Triests experienced seventy years before. Their hopeful optimism remained with us, as did the film's indelible images, as we exited the theater. In a "close encounters" panel discussion, directors Robert Edwards (Land of the Blind) and Rex Bloomstein (KZ) joined Sam Zarifi, Human Rights Watch, Asia; Robert Fischer, Filmfest München; and Marianne Heuwagen, Human Rights Watch, Berlin, to discuss Human Rights in Film. Edwards, noting that he had been asked why he made a pessimistic film that doesn't "show how you can make things better," said he felt "you have to portray things as they are," and in that regard, his film was "a call to arms." On the other hand, he added, it could also be seen as an optimistic film, because the main character did what was right; just because he suffers does not mean he should not have acted as he did. While optimism may be necessary for people who work in organizations such as Human Rights Watch, in order to be able to do the work they do, he added, for others, optimism may not be warranted in a world where governments are still establishing "ministries of virtue" that violate people's rights. Asked why he selected these particular films, Fischer replied that Land of the Blind and KZ were selected for their differences as well as for their similarities. While the first is a big-budget Hollywood film with big-name stars, and the second a film shot in digital video with a small budget and non-actors who speak, unscripted, directly to the camera, both films leave it to the viewer's own judgment, unlike films that implicitly impose one. Noting, as he did before the screening audience, that there have been over 4,000 documentaries on the Holocaust, Bloomstein observed that the motto "Never again" has become a joke, because it keeps happening again. Asked if the information obtained in the edifying interviews of the camp's tour guides was planned or serendipitous, Bloomstein replied that he shot over 150 hours of recorded interviews, so he had a good amount of material to choose from. Film is a vital tool, the panel generally agreed, because "the people who control the images control the message." Fischer remarked that while there had not been a political cinema in France for decades, suddenly, no doubt reflecting the social and political situation, there is one again. Indeed, the line-up of French films this year included two that dealt explicitly with political issues of the sixties: I Saw Ben Barka Get Killed (Serge Le Péron, France, 2005) and October 17, 1961 (Alain Tasma, France, 2005), the latter described by Keith Uhlich of Slant magazine as "a gripping... video docudrama of the infamous night when the racial tensions between the Parisian police and the Algerian underclass... came to a head." In a memorable line from that film, a young woman tells her friend: "You can pretend not to see, but once you do see, you have to act. You have no choice." That line spoke eloquently to the Human Rights films, and to others at the fest as well. Films on Human Rights Set in the tinderbox of Tangiers between the massive destruction of World War II and the riots of October 17, 1961, For Bread Alone (Rachid Benhadj, Italy/France/Morocco, 2005), based on the best-selling autobiography by Mohamed Choukri, is at once timely and timeless, with echoes that reverberate disturbingly into the present and potentially into the future. Beginning as a story of incredible deprivation and abuse, it ends as an inspiring paean to persistence, pluck and resourcefulness and the transformative power of education, while never allowing the horrors of the past to fade entirely from our consciousness. The film's effectiveness lies, for one, in its ability to meld the historical--we watch as the conspicuously wealthy French occupiers eat, drink, and party without even a backward glance at their suffering neighbors, whose urchin children beg pedestrians for food--with the personal. We see the the boy watch his mother savagely beaten by his drunken, unemployed father who, in an act of rage, smothers the younger brother for crying, uncontrollably, for food. It is also rich in imagery: In one unforgettable scene, we see the adolescent Choukri watch with hungry eyes as the daughter of his protector bathes. Stealing her panties as they hang out to dry, he nails them to a wall, tacks two huge oranges above them, and slowly, sensually, gnaws the luscious fruit. (The book, published in 1952, was banned for some thirty years in many Middle Eastern countries for its sexual explicitness.) For all its depictions of abuse and pain--the prison guards come off as not only gratuitously cruel but irredeemably corrupt, taking as much pleasure in tormenting the inmates as in robbing them--the film concludes on an emotional high note that is neither contrived nor improbable. Its ringing testament to not just the value, but the urgency, of education should make even blasé or discouraged high-schoolers rethink any reflexive dismissal of them. (If the film, which also screened at Cannes and Montreal this year, doesn't make it to our area, the book is available at the Library of Congress, the Arlington Public Library, and the Enoch Pratt Free Library in Baltimore.) All in the (immediate) family: The Makhmalbafs As Barry Levinson's films often revolve around families, Mike Figgis has wrestled with the powers that be, and human rights remains a vital topic for films from every corner of the globe, there is a single family whose lives and films join many of these elements. This year, Filmfest München presented virtually the entire oeuvre of this distinguished family of filmmakers, in the biggest retrospective of their films ever held: the Makhmalbafs.  In addition to screening their films--from the first, father Mohsen's Nassouh's Repentance

(1982), to the most recent: his Scream of the Ants (2006), which premiered there; from the

youngest child, Hana, probably the youngest cineaste to have a film presented at Venice, to the middle son

Maysam, whose premiere film was warmly received at the fest; to the eldest, the estimable

Samira, whose At Five in the Afternoon (2003) won two awards at Cannes, to wife and step-mother Marzieh Meshkini, whose Stray Dogs (below) and The Day I Became a Woman are

worthy additions to the canon--the fest also offered a thought-provoking "close encounters"

panel discussion with the entire family, conducted by Klaus Eder, Filmfest München

programmer. (To facilitate reading, Samira, Maysam, and Hana Makhmalbaf are henceforth

identified by first name only.)

In addition to screening their films--from the first, father Mohsen's Nassouh's Repentance

(1982), to the most recent: his Scream of the Ants (2006), which premiered there; from the

youngest child, Hana, probably the youngest cineaste to have a film presented at Venice, to the middle son

Maysam, whose premiere film was warmly received at the fest; to the eldest, the estimable

Samira, whose At Five in the Afternoon (2003) won two awards at Cannes, to wife and step-mother Marzieh Meshkini, whose Stray Dogs (below) and The Day I Became a Woman are

worthy additions to the canon--the fest also offered a thought-provoking "close encounters"

panel discussion with the entire family, conducted by Klaus Eder, Filmfest München

programmer. (To facilitate reading, Samira, Maysam, and Hana Makhmalbaf are henceforth

identified by first name only.)When one sees an Iranian movie, posited Eder, there is something in the language of the image that immediately identifies it as an Iranian film. An outsider who is relatively unfamiliar with Iranian cinema may see the similarities, responded Makhmalbaf, but seen "from inside," there are many differences. If there are similarities, he added, they may lie in the fact that in Iranian cinema, the cinematic image is a translation of the literary image. There is a very strong storytelling tradition in Iran. Cinema, he taught his children, like any art, is divided into two parts: what you want to say, and how you say it. How did he come up with the idea of a family of filmmakers? The family always came with him whenever he shot a film, and saw behind the scenes. Samira decided at 14 that she didn't want to go to school, she wanted to make films, and he agreed; the others followed. But it was not at all a year-round vacation. Sometimes there were 16-hour days in the car, traveling from one place to the next, meeting and learning about people of different cultures in different situations, hauling out camera equipment, setting up scenes; it was work and education combined. Samira noted that she was always a good student in school, but that education was always framed in terms of its value in getting a husband. "I wanted to do more with my life." Another thing that bothered her was that the teachers always gave her answers instead of allowing or encouraging her to find them herself. (Indeed, in Vera Tschechowa’s Salam Cinema--The Makhmalbafs and Their Films (Germany, 2005), father Mohsen says, "You go to school to learn how to be like other people. Education should [instead] teach you how to find out who you are and what you can do.") Their father wouldn't let them watch TV, she recalled, but one day she saw a program at a friend's home about two girls in Afghanistan whose father had imprisoned them in a small room in the house behind iron bars, ostensibly to protect them from the world. She was moved, seeing "how love could be hurtful, even if well-intentioned"; the story became her first film, The Apple (1997). Made at 17, in just eleven days--talk about quick studies!--it was screened in Official Selection at Cannes, and won the London Film Festival's Sutherland Trophy for best first feature. Maysam recalled how as children, he and Samira would make home movies and hide when their father came home, out of fear that they were no good. But his critiques were invaluable. You clearly love your home country, said Eder; why don't you make films there anymore? Makhmalbaf's answer was a simple one: because the Iranian government won't let him. (In fact, as we learned in the aforementioned Salam Cinema--The Makhmalbafs and Their Films, his last two films were made without the required permit for a screenplay.) But he loves his country, and wouldn't live anywhere else. Afghanistan, where the Makhmalbafs have shot several films, has a similar language and culture, and even many of the same problems, but more freedoms, he added, and so is more conducive to filmmaking. Furiously productive, he has 15 scripts he'd love to shoot. Even Samira's internationally acclaimed At Five in the Afternoon (2003) was screened in Iran in a small, out-of-the way theater for a very short period, so hardly anyone saw it. Indeed, every year they shoot three or four films, but the government will not let them be shown there. The family currently lives in Tajikistan, and their desire to move to France is stalled by that country's delay in processing the paperwork: until Iran renews their passports, France won't give them permanent visas. Samira, whose At Five in the Afternoon won both the Jury Prize and the Prize of the Ecumenical Jury at Cannes, called out from the podium: "We don't want your prizes! Give us a visa!" Asked whether he was afraid that the magic of his films may be linked to Iran, and that he'll lose it if he leaves, Makhmalbaf reminded us that Tarkovsky left Russia for Italy, and made even better films! [According to imdb.com, Tarkovsky's last film, Offret (1986), won an almost unprecedented four prizes at Cannes.] Pressure can make you weak or strong, noted Samira, like a spring: You press on it and it goes down; when it comes up again, it's stronger than ever, because of the pressure it's been under. Her father, imprisoned and tortured under the Shah of Iran ("the only thing the revolution changed was the name of the king," he says in Salam Cinema), is living proof of his daughter's philosophy. As is, it could be said, the filmic output of this remarkable family, which despite intense pressure is still producing creative cinema that is shot in other countries and embraced by cinephiles and audiences around the world, and yet remains essentially, profoundly Iranian. A look at some of those films: Serendipitously, a September 3 article in The Washington Post’s Travel section reports on the country’s love affair with Hollywood. Salaam Cinema (Mohsen Makhmalbaf, Iran 1994), not to be confused with son Maysam's similarly titled film, is an eye-opener for those unfamiliar with Iran beyond the usual media reports. The premise, Makhmalbaf tells readers of the ad he places in a Tehran newspaper, is a film to salute cinema on its 100th birthday. He invites all and sundry to audition for parts in this noble exercise, and sure enough, he is besieged with aspiring film stars--the men in jeans, the women duly dressed in full chador (and white tennis shoes)--convinced they're the next Paul Newman or Marilyn Monroe, and doing scenes, by heart, from the films that made them famous. But Mohsen is a demanding and unpredictable taskmaster, alternately bullying them, sometimes to the point of tears, to repeat lines again and again; asking them embarrassing personal, and unanswerable philosophical, questions; manipulating their emotions and morals by pitting them against each other, then excoriating them for their selfishness or ruthlessness; imperiously throwing them out, then quickly changing his mind and allowing them back in--only to throw them out again. But the tough ones last, sometimes incisively turning his own words back on him (the women are especially good at this), and even learning from his example: Told that they are good enough to take his place and audition their colleagues, two of the women swiftly put the hapless ladies through the same torment, as though they were born to it. An object lesson for Iranians, perhaps, but also for Westerners, who have a few demagogues in their own past. And an edifying, humanizing look at a people we sometimes see in dehumanizing shorthand. But then, the Makhmalbafs' films invariably offer this. Marzieh Meshkini's Stray Dogs (2004) follows a boy and his little sister through war-torn Afghanistan, where it was filmed. Told from the children's perspective, it would probably garner a PG-13 rating here (aside from some choice swear words used by the little ones, who have seen too much in their young lives), but would also be appreciated by anyone who wants more than the "nightly news" version of Afghanistan, and who cherishes good storytelling. The film opens with a group of children on their way to school, who see a cute little terrier and, as kids will, pursue him. The pup falls into a hole, and the children, at the urging of one boy begin shouting at the dog, whose breed is apparently unfamiliar to them, and throwing lit torches into the hole: "He's a foreign dog!" yells one, "he won't understand us!" "He's an American dog!" yells another, "they killed the Taliban!" Two of the children, a boy and his sister, feeling compassion and concern for the little fellow, sneak in from behind, and extricate him from the hole. But what to do with him? Take him someplace safe, of course--to prison! Where he'll be cared for, or perhaps adopted, by one of the guards or inmates. And which prison? Well that's a no-brainer: the one their mother is in! Seems she's been sent to a horrific, primitive, barren dungeon of iron and stone that houses women who have somehow displeased their husbands or the authorities. (We get the impression that situations and prisons such as these are not anomalies in Afghanistan.) Upon their reunion, the mother tells the girl, who is about five and perhaps seen as the more likely to sway the father's hard-heartedness, to go to the father to seek her release. We learn that her unpardonable offense was that, not having heard from her husband in several years and told that he was dead, she remarried. With two children to support, forbidden to work by cultural and religious (and possibly even state) law, she was in essence compelled to wed in order to feed her children. However, logic holds no sway with the father, who had her imprisoned upon learning of her marriage, and now is equally unimpressed by the children's pleas. In desperation, they decide that their only hope is to somehow find a way to join their mother in that hellhole of a prison, and are advised by a street-wise urchin to see The Bicycle Thief, which is playing at the local cinema, for tips on how to get arrested as thieves. In a wink-wink at the adults in the audience, the ticket seller warns the kids that they're probably wasting their money; The Bicycle Thief is boring, it's an art film, nothing happens in it, nobody comes to see it. However, if they're determined, he'll sell them a ticket: "The dog gets in free." The fierce loyalty of the two children to each other and their mother; their determination to stay together and find their place in a world of poverty, bleakness and desperation; the gentleness and love expressed by the little girl toward the dog--Stray Dogs may be too transparent a title, but on a very basic level, it works--and the occasional sly humor, make this a very human film. In contrast, the most magical of all Makhmalbaf films must surely be father Mohsen's Once Upon a Time, Cinema (1991), which has been succinctly and cogently summarized in "Salaam Cinema: The Films of Mohsen Makhmalbaf" (Pacific Cinémathèque, Vancouver, British Columbia): "...Once Upon a Time, Cinema (Nasseredin Shah, Actor-e Cinema) Makhmalbaf's "love letter to the Iranian cinema" (Deborah Young, Variety) is a free-for-all fantasia in the mode of Buster Keaton's Sherlock Junior or Woody Allen's The Purple Rose of Cairo, in which "characters jump in and out of cameras, projector and screens, time goes backward and forward in melancholy leaps and actors appear in multiple roles" (Young, Variety). At the dawn of the 20th century, a Chaplin- like character known as the Cinematographer introduces the magic of movies to the Iranian court. The pompous Shah, who has 84 wives and 200 children, is dead-set against the pernicious influence of movies, but at the sight of his first film he falls madly in love with its damsel-in-distress heroine, and resolves to give up his kingdom and become an actor. Makhmalbaf has described the work as a "1001 Arabian Nights" of Iranian film history, and he pays fond tribute to his nation's cinema by seamlessly and inventively weaving myriad clips from classic Iranian movies into the screwball narrative. The film won major awards at the Karlovy Vary, Istanbul and Taormina festivals. Once Upon a Time, Cinema almost defies description as the complexity and imagination Makhmalbaf brings to it produce a dazzling visual roller coaster on which to sweep the viewer along. . . [a memorable] cinematic fairy tale" (Sheila Whitaker, London Film Festival)."And a memorable cinema family. There will undoubtedly be more heard from all of them in the future. Another notable cineaste who took his place on the podium was Terry Gilliam, whose Tideland was screened. (An interview with Gilliam in which he discusses the film, appeared in the Aug. 10 Washington Post.) Since Tideland will have its U.S. premiere in New York in October, the revealing interview with Gilliam, along with a film preview, will appear in the October Storyboard. Other noteworthy films The opening-night film was the somber but moving Winter Journey (Hans Seinbichler, Germany, 2006), which teams two of Germany's most distinguished actors, Josef Bierbichler and Hanna Schygulla, as a successful, seventyish businessman plagued by depression and financial woes, and his steadfast, if increasingly puzzled wife, whose worsening eyesight causes him to grab onto an ostensible fiscal life raft that will ultimately sink him. The film is dedicated "To our fathers," and may refer to those who, in various ways, found themselves without an emotional or moral compass in the aftermath of Germany's defeat in World War II. A character at once sympathetic and exasperating, Franz, out of desperation to pay his debts and finance his wife's surgery, gets taken in by the oldest scam in the world, the one that used to be common to online inboxes: A mysterious request from across the ocean (in this case, Kenya) to allow his bank account to be used as a conduit for millions of dollars (euros), leaving him with a nice chunk of change in exchange for this (of course!) utterly risk-free service. He loses everything, and hires a young woman as translator (Sibel Kekilli, from Head-On) to accompany him to Kenya to get his money back. Poor Franz finds what we expect him to find: the photography is masterly, highlighting the searing contrasts between the magnificent landscape of the natural habitat, and the merciless devastation of the empty construction site--the address he was given--surrounded by dilapidated buildings and grinding poverty. He seeks aid at the German embassy, where he is told in no uncertain terms to go home: these people play rough, and his life could be in danger. One of the most compelling moments in the film is the heartbreaking resignation with which Franz sits at the piano in a restaurant/bar and sings the haunting "Der Leiermann" (The Hurdy- Gurdy Man) from Schubert's song cycle "Winterreise," which encapsulates his depression. The young translator and the embassy official weep; the woman beside me started crying too, and soon, pockets of quiet sniffles were heard through the theater. In Griffin Dunne's Fierce People (USA/Canada, 2005), a deceptively benign "tales of the rich and brainless" metamorphoses into a contemporary coming-of-age story, implicitly juxtaposing the savagery of the culturally fierce--the teenaged Finn's estranged father is an anthropologist studying the jungle-dwelling Ishkanani--against the savagery of the fiercely cultured. Or at least the wealthy: the family, (ostensible) friends, and hangers-on of Finn's junkie mom Liz's wealthy "sugar daddy," the improbably named Ogden C. Osborne, who invites the two of them to his estate to help get their lives back on track. With Diane Lane as Liz and Donald Sutherland as Osborne, and impressive turns by Anton Yelchin as Finn and those playing the young cave dwellers who will inherit their parents' powerful if morally dubious mantles, Fierce People would have been worth a visit for its cast alone. And if at times it feels a bit like Henry Aldrich meets Lord of the Flies, and its messages are similarly mixed, that may be by design: what better way to bring home to us, who occupy neither of those worlds, the inherent and unexpected richnesses and contradictions of not only their lives, but ours... In a podium discussion, director Dunne, whose acting career has spanned more than 50 roles in films such as Johnny Dangerously (1984) and Quiz Show (1994), and whose directing efforts include Addicted to Love (1997), explained how the film came to be made. The author of the book, Dirk Wittenborn, had asked Dunne and a few other people to read his manuscript and give him ideas on how to end the book; he was at a loss. Recognizing its filmic potential, Dunne quickly optioned it, attracted by both its coming-of- age and "poisonous orchid" aspects. How did he obtain his stellar cast? He began with Diane Lane, whom he knew he wanted, then Donald Sutherland approached him to play the role of Osborne, having read the script; the hardest part was finding the young man to play Finn. Dunne expressed great satisfaction with young Yelchin, perhaps best known known for his Byrd Huffstodt in the TV series "Huff," and Kristen Stewart (Finn's girlfriend Maya), who played Jodie Foster's daughter in Panic Room (2002). By coincidence or design, there is much in The Treatment (Oren Rudavsky, USA, 2006) that recalls Michel Gondry's The Science of Sleep (reviewed in the April Storyboard, and currently screening at E Street Cinema). As in that film, there is an arresting, abstract tableau of colors, shapes, and motion, here as background for the screen credits, while the plotline encompasses both the classic Hollywood guy-gal pushme-pullyu and the lead character's use of unconventional therapy to solve personal problems. The Treatment is the story of a young New York schoolteacher for whom nothing seems to be going right--his girlfriend has called it quits (and called him a few things in the bargain), his relationship with his father seems to be hanging by a thread, his professional and financial life are falling apart at the seams--and who seeks to solve his problems through psychoanalysis. Unfortunately, the shrink he picks is, as Village Voice succinctly puts it, "a maniacal Freudian... therapist from hell." Be that as it may, it is he who arguably gets the best line. Berated by his whining client for having failed to solve his problems, the doc looks him squarely in the eye and tells him: "My love is not a shield; it is a sword." If he got only that out of the sessions, IMO, it was worth every miserable minute! Another Filmfest focus was Quebec; six films were shown. One of these, not seen since its premiere at the Toronto film festival ("We really had to fight to get this picture"), was Philippe Falardeau's Congorama (Canada/Belgium/France, 2006), which comprises two complex tales, intricately told. Michel, a Belgian inventor, finds out from his elderly father that he's adopted. Determined to find his birth parents, he travels to Quebec, where, the father has told him, he was born in a barn. There he (literally) runs into Louis, an electrical engineer driving a prototype car, whose father, we later learn, was a brilliant inventor cheated out of recognition for his groundbreaking research: a wrong which Louis is determined to right. The film is elaborately constructed, with abrupt narrative and temporal shifts between present and past, and from Michel's story to Louis's. Despite its serious themes, it does not lack for wit, which the actors skillfully pull off with seeming ease. (There's also a humorous bit with an emu who, apparently much like deer here, gets in the way of the car. "No emu," the end credits assert, "was injured during the making of this film," followed by a shot of a very alert bird.) At a Q&A with the director, Falardeau (who also wrote the screenplay), reproached by a perplexed audience member for leaving the ending ambiguous, said he decided not to tie up all the loose ends, because, after all, "that's like life." Nor, one suspects, would the subject of Oscar-winning director Frieda Lee Mock's Wrestling with Angels: Playwright Tony Kushner (USA 2006). Kushner, whose multiple distinctions include the Pulitzer Prize for Drama and two Tony awards, and whose Caroline, or Change played to rave reviews at Studio Theater this summer, deeply impressed Mock with his improbably inspiring, 60-second, impromptu commencement address at her daughter's 1999 Wesleyan graduation. Perhaps spurred by the rousing reception it received, Kushner delivered one to Vassar's 2002 graduating class, which was taped and included in the film. Classic Kushner, it used humor and pith to tell them, in a word, to act. And act is what Kushner does, when he's not writing (and, come to think of it, when he is). The film follows him over a three-year period from the fall of 2001 through November 2004, and includes personal and professional observations from friends, family and associates--and of course, from Kushner himself. We hear that he learned playwriting at the knee of a Brechtian at NYU, that Angels in America was originally seven hours long, and that he writes in longhand--but very quickly. We learn how he got his elderly father to accept his homosexuality, and we hear snippets of impassioned speeches and radio commentaries on gay rights. In one of the most edifying and moving parts of the film, we meet a woman who as a child appeared in the notorious Theresienstadt propaganda film--produced by the Nazis in 1944 to deceive the Allied nations into believing that concentration camps were more or less like day camps--and who was one of the few survivors of the camp. In Mock's film we see a scene from it, with rows of grim-faced children in costume singing a happy little ditty from the play Brundibar, written in the Prague ghetto in 1938 and performed more than 50 times by the children of Theresienstadt. The score was saved; the play has been performed around the world, and in present-day Munich in memory of the children. Kushner and his friend, renowned children's author Maurice Sendak, collaborated on a storybook (Brundibar, Michael Di Capua Books, November 2003) that tells this tale which, in a devastating irony, "succeeds both as a simple children's story and as a compelling statement against tyranny" (from amazon.com's entry on the book; Steven Engelfried, Beaverton City Library, OR). Despite the anguish and conflict that inform his plays, Kushner in principle will not portray his characters or their conditions as hopeless; it is, for him, an "ethical obligation to include hope." Hope was in short supply for the victims of serial killers Martha Beck and Raymond Fernandez, whose bloody trail is brought vividly to life in Todd Robinson's Lonely Hearts (2006), Filmfest München's closing night film. In a podium discussion just before the screening, Robinson told of his personal connection to the story, and offered insights into his working methodology and philosophy, as well as some behind-the-scenes scoops. The film's all-star cast began with James Gandolfini, who really wanted to do the film, Robinson told us; his name helped pave the way for other big-name stars (including John Travolta, Salma Hayek, and Laura Dern) to come aboard. The fact that Robinson has the same last name as that of the detective played by Travolta is not coincidental; his grandfather was in fact Elmer C. Robinson, the policeman whose participation in the case is the film's nexus. Growing up with this knowledge, he thought his grandfather's role in the case would make an interesting film, Robinson said. His own entry into the business was precipitated by dyslexia, which made the computer and word-processing tools such as SpelChek "linchpins" that facilitated writing; and he found that he loved to write. His grandfather didn't talk about the case, except within the family. Living with death and horror had an inevitable effect on his grandfather's family life, said Robinson, who called it "a common concern" that affects him, and indeed all people with intense jobs they cannot help, to an extent, bringing home with them. When it comes to directing, Robinson's philosophy is that you "wait for the mistakes to happen," because "the best things are unplanned." Asked by an audience member if he had a philosophy about depicting graphic violence, Robinson acknowledged that there is a scene in the film that's "incredibly graphic," but contended that it needed to be shown because "it was important to know these characters, and what they were capable of." And while there is no reason to be gratuitous, "I'm very comfortable with people being uncomfortable." Asked about the cinematography, Robinson said Peter Levy, the cinematographer, shot Lonely Hearts in Super 35 Panavision, and modeled it after the films of William Wellman. Textures and colors were very important, and desaturation was used to visually situate the film in the postwar era. Reflecting on his stars, Robinson said that with John Travolta, "You feel [his] star presence." He had certain ways of working, said Robinson, which had to be accommodated. Gandolfini is a TV veteran, and is used to working quickly, which was a distinct advantage in shooting the film. As for Salma Hayek, Robinson conceded that she is not the physical embodiment of the real Martha Beck, who was huge and stocky. But the heavier actors he approached were reluctant to play such a hateful, vicious person, who for years had been a victim of serial incest at the hands of her brother. Apologizing for not being Salma Hayek, who couldn't make it to Munich, or to Tribeca, where Lonely Hearts premiered in April, Robinson explained that she's "a very busy woman." The Filmfest programmer wholeheartedly concurred, noting that Hayek was in four or five films at this year's Filmfest. One of these was the directorial debut of Oscar-winning screenwriter Robert Towne Ask the Dust, which had a limited release in March of this year. Based on the masterly, and largely autobiographical, 1939 novel by John Fante, Ask the Dust recalls the noirs of the forties and fifties with tight framing and jagged light-and-shadow patterns, and the melodramas of the twenties and thirties with narrative constructs of romantic conflict, and dolly shots that swiftly distill the tragedy of doomed love. Its tale of the unlikely, undying, and impassioned pairing of aspiring writer Arturo Bandini and Mexican waitress Camilla Lopez both personifies and humanizes the ethnic tensions of thirties Los Angeles, whose palpable heat limned in moody desert hues make the city almost a character in itself. If ever a city were a character in itself, it would be, n'est-ce pas? Paris. But Paris is, hélas! a minor one in Bertrand Blier's Combien tu m'aimes? (How much do you love me?, France/Italy, 2005), whose amusingly apropos title can, and should, be read both ways. A film soufflé, it tells of French everyman François, who wins the lottery big time and decides to ask a gorgeous Italian call girl (Monica Bellucci) to live with him for 100,000 euros a month. One of the unalloyed delights of the film is the way its score explodes with excerpts from the most beloved and passionate Italian operas at the most unlikely, but perfectly placed, times. In one, a sumptuously sung aria from "Madame Butterfly" accompanies Bellucci's luxurious emergence from her cocoon--actually, what looks like a full-length fox fur (hopefully a faux fur!). Resplendently dressed in a low-cut, curve-hugging, white satin gown, revealed in all her curvaceous, raven-haired, sex-goddess beauty, la bella Bellucci is bathed by an incandescent, almost heavenly light. In stark contrast, Yves Angelo's Grey Souls (France, 2005) is a mournful, thoughtful, elegantly paced film for which the horrors of war are both backdrop and agent of the inhumanity that blackens the spirits and actions of a small French town in the midst of World War I. The characters are indelible: An angelic child, curiously named Belle de jour, whose body is found in the film's first minutes, and the slimy prosecuting attorney whose "methods" force an innocent man to "confess" to the murder... A young male teacher who completely loses it in front of his class (mental and emotional battle scars, or reaction to the insanity that surrounds him?), and the young female teacher who replaces him, and whose gentle ways and positive outlook are fatally challenged by news she had hoped against hope never to hear... The learned and gruffly authoritative mayor who offers her a cottage on the grounds of his home, and whose compassion is masked by a secret despair which, when revealed, holds the key to many heretofore unanswered questions... With the close of summer just around the corner, it may be fitting to close this report with a film that will register with anyone who has ever taken a package tour with a bunch of strange (the operative word here) people--a film that may not get to DC cinemas (although it screened at Tribeca last spring, garnering a Best Actress award for Eva Holubovà and a "Special Mention" for the entire cast), but that DC viewers would definitely "get" if it ever did. Holiday Makers (Jiri Vejdelek, Czech Republic, 2006) takes us along for the bumpy ride on a tour bus with a group of Czech vacationers who seem slated for what another reviewer has aptly called a "holiday in hell," each packing his own hopes, expectations, histories, and hang-ups. The film begins with a spellbinding underwater sequence which both introduces us to the Adriatic paradise for which our travelers are bound, and subtly suggests that the essential in the human dramas we are about to encounter lies beneath the surface. From the beginning, the martinet of a bus driver, distributing brown plastic cup holders and white plastic cups as if to a group of schoolchildren--one apiece, and woe betide anyone who loses or breaks one!--demonstrates the endurance of the communist legacy for those who no doubt mourn its loss, while the passengers humorously ignore his threats. The characters are so realistically delineated and the situations in which they find (or put) themselves ring so true, the viewer not only comes along for the ride, but by the time it ends, almost feels like part of the family. There's the beautiful woman, who simply wants to strike up a friendship with the handsome singer who can't see the honesty in her overtures, and just thinks she wants to bed him; the 12-year-old boy, relentlessly ridiculed and called gay by his teenage nemesis, and, not having felt sexual stirrings of any kind yet, agonizes throughout the film, until a wise older woman who knows what it is to be called "different" teaches him, in one of the time-honored ways, that he's not--the portraits are by turns humorous, instructive, and compassionate, gently though pointedly shattering stereotypes, both theirs and (if we hold them) ours. What is most striking, perhaps, is that for all its incisiveness the film is never judgmental, but is instead a wry and affectionate, if cautionary look at a random, disparate group of people; by extension, at us, our friends and neighbors. In a way, that is also the key to Filmfest München's success, and to the affection and loyalty it inspires. It opens the world of film and its makers and through them, the world, to people of different cultures and countries, who not only watch them together, as at other major film fests, but who can sit six feet from those who made the magic possible--even run into them on the "Isar Mile" connecting all the cinemas--and interact with them, one on one. "Today, I find myself missing so many of the people from Filmfest!" wrote director Steve Palackdharry (Journey to Justice) shortly after the festival. "Though I believe I am now home, I feel that I have left another one." A pretty common feeling among Filmfest aficionados. Hope to see you there next year! Visit the website which has lots of pictures. Call for Applications Young Film Critics Invited to Berlin

Young film critics and film journalists are invited to apply for The Talent Press to report on the films at the 57th Berlin International Film Festival (February 08-18, 2007) and on the events of the Berlinale Talent Campus (February 10-15, 2007). The Talent Press is a project of the Berlinale Talent Campus, Goethe-Institute, and FIPRESCI (the International Federation of Film Critics). We Need to Hear From YOUWe are always looking for film-related material for the Storyboard. Our enthusiastic and well-traveled members have written about their trips to the Cannes Film Festival, London Film Festival, Venice Film Festival, Telluride Film Festival, Toronto Film Festival, Edinburgh Film Festival, the Berlin Film Festival, the Munich Film Festival, and the Locarno Film Festival. We also heard about what it's like being an extra in the movies. Have you gone to an interesting film festival? Have a favorite place to see movies that we aren't covering in the Calendar of Events? Seen a movie that blew you away? Read a film-related book? Gone to a film seminar? Interviewed a director? Taken notes at a Q&A? Read an article about something that didn't make our local news media? Send your contributions to Storyboard and share your stories with the membership. And we sincerely thank all our contributors for this issue of Storyboard. Calendar of EventsFILMS Previous Storyboards

August, 2006 Contact us: For members only: |

Driving Lessons (Jeremy Brock, UK, 2006) had its World Premiere at TriBeCa and its European Premiere at the Edinburgh Film Festival. It is scheduled for previews and release in September.

Driving Lessons (Jeremy Brock, UK, 2006) had its World Premiere at TriBeCa and its European Premiere at the Edinburgh Film Festival. It is scheduled for previews and release in September. This year's

This year's